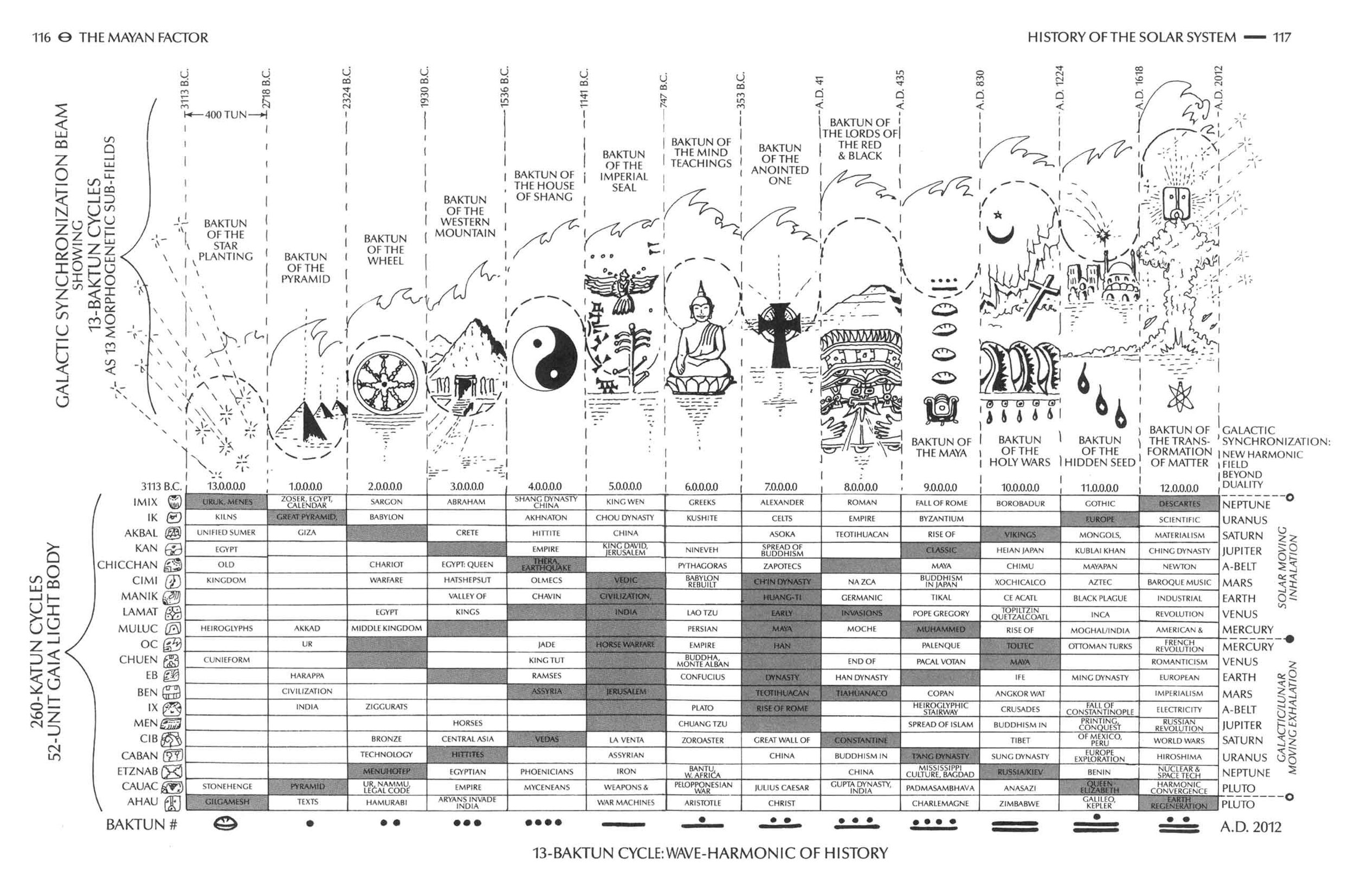

Seven years ago, on December 21, 2012, the World was supposed to end. It didn't, and I require finding relevance to a prophecy I expected to materialize. With the ensuing critical distance since this non-event, I believe that what the Mayans predicted was the end of History. Vilém Flusser, probably unaware of this Mayan prophecy, proposed a similar scenario fueled by technology, more specifically, by technical images. Flusser's interest in the End of History parallels José Argüelles' theories of a posthistorical period. Both thinkers used the term Posthistory in the same manner. Simultaneous to Flusser's coining of the universe of technical images, Argüelles was putting together a narrative that revolved around the Mayan Calendar and its cycles. Flusser believed that information was negative entropy, increasing order and originality in processes which fight against the universal descent into disinformation and chaos. For him, technical images were destroying the linear nature of History and causal effects, leading to a new epoch in human life characterized by the exhaustion of conventional linear, causal, narratives: History.

Respectively, Argüelles thought that the effect of energy factored with the passage of time resulted in what we call Art. His formula A=t(e) summarizes that both humankind and the universe tend to create beautiful entities, beings, processes, ideas, even dreams; when given enough time. Argüelles was obsessed with Mayan Calendrical inscriptions and interpreted them as pointing to the end of a 5,200-year cycle in 2012. He saw the completion of that cycle as the end of the historical domain on Earth, not the end of the World. Argüelles envisioned a post-technological world in which humanity was able to finally connect to the center of galactic knowledge, the Hunab-Ku. This cosmic center would be in flusserian language the utopic scenario of absolute human playfulness (homo ludens) facilitated by technology, the center of our cosmos being the cloud of infinite information at our disposal. The adverse outcome in Argüelles' worldview is the fall of humanity caused by a mechanical, money-driven, anti-natural mindset, in which human energy diverts from its creative destiny and engenders asynchronous, harmful, destructive happenings: entropic Art. In flusserian terms, this would mean an unbearable increase in entropy and disinformation that leads to darkness and extinction. In short, conscious energy creates, in the flusserian view, Information; in Argüelles' perspective, that same conscious energy creates Art. The World runs on Art, Information, and their opposites.

Argüelles' most dramatic action was his campaign for calendrical reform. He viewed the Gregorian Calendar as an irregular measuring tool that was not in accord with natural cycles. He even blamed the increasingly worrying disconnect of humans to nature as a result of the mental program established by the Gregorian Calendar, a program based on accounting and a military mindset, not on natural cycles. He saw a better option in the lunar calendar used by the Maya, composed of thirteen months of 28 days each, evenly distributed, with a Day Out of Time, happening at the end of every cycle (July 25). With this reform, human life would be more attuned to nature again, and we would all have a lunar, feminine, regular calendrical backdrop for experience.

Photography, the first flusserian post-Historical image, has a peculiar relation to the calendar. It has no direct connection to it, and the dating of images happens either in the metadata of the photograph's file or in the date imprint in film cameras (in this case the picture gets a permanent textual mark). Hence, by being an image, Photography operates partially outside of the historical domain. Yet, photographs are generated based on the foundations of the calendar, and they are created in fractions or increments of seconds, the very fabric of the calendar is embedded in each photograph, they are energy factored by time, technology that abstracts scientific texts and the calendar to yield an image. In Argüelles' terms, Art; in Flusser’s, Information. Posthistory has enthroned the photograph. Photography has become a bored and cruel ruler. Never has Photography had so much power to alter our lives: instill desire, envy, exert influence; it keeps us scrolling endlessly. It establishes the image of the epoch, an image of endless unfulfilled, uncomfortable, algorithmic desire.

The new channels of Image+Text distribution have rendered traditional ones (journalism and Art) impotent. Photographic delivery happens primarily on the web, replacing traditional media and the even older visibilization of images in the public space. Public photographs are now experienced privately in our customized screens. They constitute an Image+Text construct composed of an image, calendrical information, and text. The Maya created objects with the same formal features. They erected stelae carved in stone, displaying images, dates, and events for their inhabitants to view, establishing official narratives and propaganda. The stelae are transitional objects created by a pre-historical society that lived in a magic and mythical World. They are transitional because they began to introduce a historical consciousness into a myth-driven civilization in which authorities controlled image production and inserted a historical consciousness by dating their monuments. They determined the number of images to be displayed publicly to build an identity and reaffirm power. Stelae served the purpose of reinforcing the connection of the ruler to the supernatural, to the gods. Therefore, only the ruler was worthy of being represented. Gradually, the aspiration was to win the ruler's favor to achieve representation worthiness. The progression of this was the dilution of the influence of these images by their proliferation, the more images displayed publicly, the less power both image and ruler could exert. That principle could still be applied today. Power is as fragmented as the number of photographs that circulate in the world.

The electronic universe of technical images is the new public square; it is the flusserian photographic universe, filled with mostly impotent pictures. All viral imagery that combines photographs, captions, hashtags, and dates are the new stelae. They exemplify the emergence of the Image+Text epoch, a period characterized by the powerful yet irrelevant seductiveness of the image. The image, commonly believed to be worth a thousand words, now leans on written language to corral its polysemous and anti-historical nature. It is almost as if photographs do not want to be images anymore; they aspire to the specificity of both documents and text. The first post-historical image longs for its historical genesis. We want them to be worth just a couple of concise and persuasive sentences, informative poetry. Like the stelae, which marked the transition from mythical to historical, Image+Text photoworks are transitional objects as well, marking the shift from History into the uncharted, potentially chaotic realm of Posthistory.

The diversion of History is ending, and we go back to a non-linear two-dimensionality, one that is merging magical thinking with a degree of historical consciousness that empowers technical images and creates new beliefs. The new imagined realities, along with its constructed narratives will shape the future of the World. We abandoned the rules of linearity and decided everything by delaying the inevitable and prioritizing the improbable. We compute our way into the future, assessing our increasing personal, social, and environmental technical debt. The universe of Image+Text objects are reservoirs that trick us into claiming a parcel of both immortality and morality. Resorting to text aims to refute the automatism inherent in image production, it is a cry to reclaim the agency and insert information into our projects. We all want to have the cake and eat it too. Predictably, we want to demonstrate how improbable we are, how informative we are. Since technical images brought contempt towards depth, text is needed to attest to the depth of our thoughts, little do we know that this depth is coming from within the confines of our technological programs.

In an epoch in which images run wildly, reflection and philosophy can only happen by engaging in that dialectic practice of creating images to inspire language, so we can conjure the stories that lead to redemption. Flusser and Argüelles represent how we must never cease to prophesize. We all are posthistorical oracles.

A virus has presented us with the first authentic global posthistorical crisis. Political leadership (except in some countries with female leadership or non-western societies) proves being desynchronized with historical precedents of resolve in times of hardship. Politicians are focusing more on how this time will be remembered in future accounts than in its pressing reality—the burden of History weights upon them reaffirming already erratic reactions. There is a tendency of trying to erase History before its very conception, deflecting responsibility in a pseudo-pluralist fashion, disowning agency over history-writing; entire states receded into historical obfuscation.

Posthistorical protests contradicting the tradition of science show us disconnect is a disease that spreads from the top down. The greatest nemesis of a new global mind is the weight of historical entitlement. Groups miss the labor of others they exploited and relied upon.

However, appreciation flows towards long-overlooked sectors, I salute garbage collectors, respect enormously the Oxxo cashiers, and empathize with vagrants who cannot shelter in place. This story is a tragedy. Coincidentally, this crisis has removed the spectacular from the spotlight, making fame irrelevant. However shortlived this moment proves to be, it engenders grief and celebration in almost equal measures.

In economic terms, several statements that claim occurrences happening "for the first time in History..." populate the media daily as of late. This obsession with the appearance of a prime situation (in the Kluverian connotation linked to originality) is misguided; we cannot measure the current march of events with a historical yardstick. We are beyond History, so bafflement is the only response to trying to fit wild statistics into a new reality. The symbolism of oil achieving a negative monetary value –less than zero– reads like poetry. The present is all about the entropic prime, it is composed of never-before-seen situations. A new yardstick for measuring historical happenings has to emerge in simultaneity to the new world order.

Therefore, the atmosphere consists of disrupted tendencies; the veil of comfort in the predictability of events has been lifted. Seven years after the end of the Mayan Long Count, we taste forced sips of the posthistorical cool-aid. Millions of people, sheltering in place and in privilege, experience a detachment from the Calendar, that accepted abstract convention that makes us exploit ourselves and the planet's resources. Those millions find themselves anxious, unemployed, at-risk; or bored, disrupted, shut-in. Many have rediscovered cooking, baking, embracing boredom, eating with no rush for the first time in years. This frequently happens in communion with others, in a diffuse and endless holiday.

Walter Benjamin believed holidays operate outside the Calendar, becoming days of remembrance. He considered them “places of recollection left blank”1] in which “the man who loses his capacity for experiencing feels as though he is dropped from the Calendar. The big-city dweller knows this feeling on Sundays.”2] This feeling of a permanent Sunday by the halt to the economy permeates the lives of cities these days. By "dropping man from the Calendar and annihilating his historical consciousness,”3] remembrance becomes king.

After quoting Baudelaire, Benjamin concludes that

the bells, which once were part of holidays, have been dropped from the Calendar like the human beings. They are like the poor souls that wander restlessly, but outside of History. 4]

Being dropped from the Calendar and History might constitute a blessing in disguise. Millions experience the current everyday in a way more related to José Argüelles' concept of the Day Out of Time. That day at the end of every 364 day-long count, a day removed from all calendrical experience, a day of remembrance and non-action.

Wouldn't it have a sense of poetic justice to drop the Calendar now it has dropped us? Become the dumper, not the dumpee?

George Eastman, the man who founded Kodak and introduced photographic practice into the fabric of the everyday, believed the Gregorian Calendar did not work. By living and breathing what Vilém Flusser would call the "first posthistorical image," he became a protagonist of the conquering of the world by technical images. He knew photographs were going to disrupt historical-calendrical thinking, altering Benjamin's aforementioned historical consciousness irreversibly. Eastman supported a movement for Calendar reform actively, to the point of using the International Fixed Calendar in Kodak from 1928 to 1989. Eastman endorsed a campaign that claimed the Gregorian Calendar is a bad habit. According to the International Fixed Calendar League the Gregorian monthly structure is

a wholly irrational division of time. It has no relation to anything in astronomy, or human experience. It is an inaccurate and varying measure of time that is a constant annoyance in business and a misleading unit in science. It has no religious significance. A month is nothing but just a bad habit. 5]

These past months have felt just like that.

Eastman went as far as to host the U.S. Office of the Fixed Calendar League in the same building as the Kodak headquarters, Posthistory Inc. Global HQ. We could assume Eastman had foreseen a posthistorical drift beginning during his lifetime, poised to continue beyond, and probably believed the irregular Gregorian Calendar would only widen our rift concerning the cycles of nature and their connection to human temporality.

Kodak stopped using the thirteen-moon Calendar in 1989, José Argüelles died in 2011 before the day he spent his entire life waiting. Kodak went into bankruptcy in 2012. All these lofty ideas became anecdote.

This past month, I have felt the Benjaminian drop from the Calendar. I have also felt the irregularity mentioned by the Fixed Calendar League, I struggle to remember which day I am living, or find the attempt to differentiate futile. I have witnessed the eclipsing of time –similar to the ending of Michaelangelo Antonioni’s film L’eclisse, quite popular in the fine-art photography scene– when commuting in a space where all activities end at dusk and the quiet golden hour is populated with dispersed urban ghosts looking for shelter from the approaching nighttime, just like in the old days.

The act of taking photographs and documenting the current urban atmosphere has felt like taking photographs on a permanent January 1. All the photographs I have taken during the quarantine have, just like us, been dropped from the Calendar and History. It is difficult to link them to a tradition, to a sequence, to History. They feel so new and so lost, they do not know what kind of document they are or how relevant they will possibly be, given we do not know what the everyday will look like after this. Photographs are, for the first time in History, pure time.

A kingly virus erected itself as an agent of change in the way we measure time, life, and the seasons. It demolished the habitual backdrop for human experience, placing the entire world, until further notice, within the darkness of an eclipsed History.

[1] Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations (p. 184). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations (p. 185). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

[5] Shall We Scrap Our Calendar? The Outlook, September 28, 1927, pp. 109-112.